RNA palindromes, including pre-miRNA, can direct embryogenesis and regeneration because they can pair with others of the same sequence.

Specific same-sequence RNA palindromes displayed in hairpin configuration on the surface of differentiated cells could unfold and pair with each other, thus triggering a cascade of molecular events that causes identical differentiated cells to stick to each other during embryogenesis and regeneration.

The same pairing by specific palindromes could ensure that synapses between neurons are correctly matched.

RNA palindromes can form hairpins

Each half of an RNA palindrome can pair with the other half, forming a ‘hairpin’, as Figure 1 shows. This figure shows two identical palindromes in hairpin configuration. One is colored blue and the other purple.

Figure 1. Two identical palindromes in hairpin configuration

Identical palindromes can pair with each other

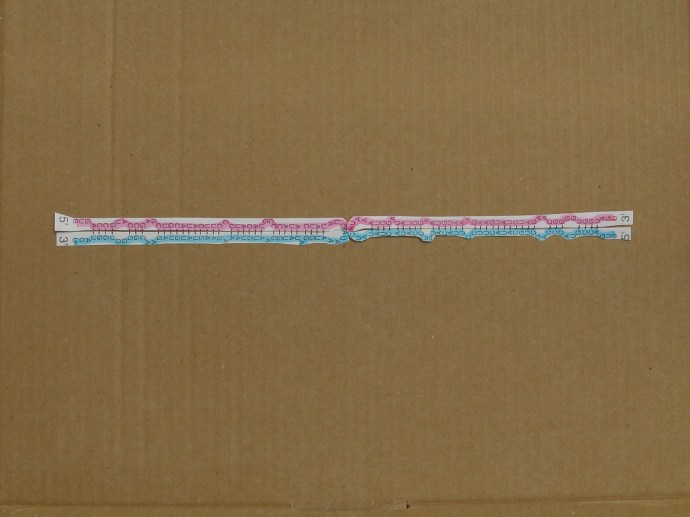

Two identical RNA palindromes can pair, as Figure 2 shows. The blue hairpin and the purple hairpin have straightened out and paired with each other.

(In preparing the illustration the paper has been cut in order to straighten the hairpins but this is not intended to imply that the hairpins are cut. The straightened-out blue strand is continuous and the straightened-out purple strand is continuous, and they pair with each other.)

Figure 2. Two identical RNA palindromes in straightened-out configuration pairing with each other (the purple palindrome is continuous and the blue palindrome is continuous, and there is no covalent bond between the two palindromes)

Specific RNA palindromes might be displayed on the surface of cells

If two differentiated cells of the same type displayed a specific RNA palindrome on their exterior surface they could recognize each other as being of the same type. Recognition would happen when the hairpins on each cell unfolded and paired with the hairpins on the other cell.

The big change in configuration from hairpin to straightened-out could be ‘sensed’ by a molecular complex anchored in the exterior cell wall that displayed the RNA palindrome externally. This ‘sensing’ would trigger a cascade of intra-cellular molecular reactions that culminated in the cells sticking to each other.

Another way in which the pairing of RNA palindromes displayed on the surface of cells might trigger a cascade of reactions that caused the cells to stick to each other is simply that paired palindromes might be strong tethers:

The architecture of organs

Thus as cells multiplied, differentiated and migrated during embryogenesis they could recognize and stick to other cells of the same type and form a homogeneous tissue.

The same process could create non-homogeneous tissues consisting of two or more types of cell arranged in particular orders. For example, a transition from one type of cell to an adhering second type of cell could be achieved if the second type of cell displayed two different specific RNA palindromes on its external surface; one identical in sequence with that displayed on the first type of cell, and the other different in sequence. Provided that the number of pairings of palindromes on the two types of cell exceeded a threshold the cells would stick together.

Then cells that displayed only RNA palindromes of the second sequence could stick to this transitional layer of cells, and to each other, thus building up a thick layer or bulk of cells of their own type.

Some types of cell might display three or more specific sequences of palindrome on their surfaces.

Processes of this sort during embryogenesis (and during the regeneration of lost body parts in some species) could arrange many different types of cell into complex architectural patterns within organs. The detailed architecture created would depend on the timing of the switching-on and switching-off of the transcription of RNA palindromes of specific sequences in the nuclei of differentiating and migrating cell types.

It might also depend, in cells that displayed more than one specific sequence of palindrome on their surface, on the rates of transcription of each palindrome, and these rates could be influenced by the local concentrations of guide chemicals and hormones.The proportions or ratios of displayed types of palindrome would change according to the local concentration of guide chemical, and this might help to shape a tissue into an organ, because only cells with the same or similar ratios could stick to each other.

Exploration of the detailed architectures that might be created by these processes would be greatly assisted by the insights of mathematicians, who might find in this new field stimulating challenges for years to come.

Ensuring correct connections between nerve cells

The mechanism described above for directing the architectural arrangement of cells in organs could also direct the architectural arrangement of synapses between presynaptic and postsynaptic neurons.

A functional synapse might not be formed unless the presynaptic and the postsynaptic neurons displayed on their adjacent surfaces RNA palindromes of the same specific sequence.

Then the hairpins would straighten out and pair with each other, and this big change in configuration would change the configuration of the molecular complex displaying the palindromes and trigger a cascade of molecular events in the presynaptic and the postsynaptic neurons that culminated in the formation of a functional synapse between the two.

It is possible that more than one specific RNA palindrome might be involved in synapse formation. If several were involved the number of mathematical combinations, or, possibly, permutations, of different sequences could be very great. The total number of pairings of straightened-out RNA palindromes would have to exceed a threshold before a functional synapse were formed.

Where would the RNA hairpins be gripped by the molecular complex anchored in the extracellular membrane?

A likely site would be the loop of the hairpin, which is composed of non-pairing nucleotides. This is the site where the configuration of the hairpin would change the most, as it straightened out. If the membrane-anchored complex (presumably a complex of proteins) gripped the loop of the hairpin it would best ‘sense’ the change of configuration of the palindrome.

Alternatively they might be gripped by one of their ends.

Pre-microRNAs might be the RNA palindromes directing embryogenesis and synapse formation

Pre-microRNAs (pre-miRNAs), are not perfect palindromes, but they might be nearly enough perfect to do the work described above. The RNA palindromes shown in Figures 1 and 2 are a pre-miRNA.

(A pre-miRNA molecule is synthesized as a long RNA primary transcript known as a pri-miRNA, which is cleaved in the nucleus by the ribonuclease Drosha to produce a characteristic stem-loop structure of about 70 base pairs long, known as a pre-miRNA).

Pre-miRNAs destined to be displayed outside the cell would have to be protected from the ribonuclease Dicer in the cytoplasm by a porter-complex that would carry them to the molecular complex anchored in the extracellular membrane, which would display them on the exterior surface of the cell.

Dicer cleaves pre-miRNA into short double-stranded RNA fragments called microRNA (miRNA). These fragments are approximately 20-25 base pairs long with a two-base overhang on the 3′ end. Dicer facilitates the activation of the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), which is essential for RNA interference. By this interference an miRNA can depress the translation into proteins of the messenger RNAs of hundreds of genes.

Perhaps embryonic cells do not express Dicer and can therefore synthesise proteins, and grow, multiply and differentiate, very quickly. In the absence of Dicer the pre-miRNAs that direct the architectural arrangement of cells and synapses would be able to reach the exterior surface of their cell wall and be displayed.

When embryogenesis has been completed Dicer might be expressed at a high level and the rate of expression of many genes slowed to a rate adequate to maintain mature tissues.

Copyright © 2016 Rivergard